Goosby v. Town of Hempstead

Landmark Lawsuit

Learn more by clicking here:

https://longisland.news12.com/hempstead-town-councilwoman-dorothy-goosby-reflects-on-making-history-in-1999

Goosby v. Town of Hempstead was a case in which Hempstead, New York’s racially discriminatory at-large voting system was contested. A transformation of the voting system was forced on the Long Island town as a result.

Description The population of Hempstead, New York, which covers the heart of Long Island’s Nassau County, is 13 percent Black and Latino, but all of its six Republican council members lived in predominantly white neighborhoods. In February 1997, a federal judge ordered Hempstead to replace its at-large voting system with six geographic districts, saying the current system “invidiously excludes Blacks from effective participation in political life.”

The original class action suit was filed by the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR) in 1988, alleging that the at-large electoral system diminished the voting power of Blacks and Latinos in Hempstead in violation of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, as well as the Fifteenth, Fourteenth, Thirteenth and First Amendments. Hempstead has a history of racially polarized voting, leaving candidates of color unable to obtain sufficient votes outside their communities to win election.

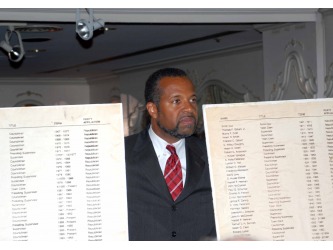

A map presented by CCR’s expert witnesses dramatically illustrated the near-total residential segregation in the township—“just like apartheid in South Africa”, according to a lawyer for the plaintiffs—a factor that ironically could make it easier to design a single electoral district where people of color may elect someone of their own choice, even by the standards of recent court decisions restricting the scope of the Voting Rights Act.

Hempstead has a poor record on race: the township was still using a literacy test for voters in 1971, several years after Congress outlawed such tests. Hempstead officials have refused to discipline employees who used racial slurs, have no affirmative action program or city human rights commission, and have never issued any resolution in support of minority issues.

“This case is not about electing a Democrat,” plaintiff lawyer Randolph Scott-McLaughlin told the appeals court. “It is about allowing minorities to acquire the opportunity to nominate and elect the candidate of their choice. Now, they don’t have a choice.”

The Court of Appeals echoed this sentiment in its decision: “Without access to the Republican slating process, Blacks simply are unable to have any preferred candidate elected to the Town Board, given the historical success of the Republican Party in all Town Board elections.”

The U.S. Supreme Court declined to review the decision of the Second Circuit Federal Court of Appeals affirming the district court’s finding that the voting rights of minorities had been flagrantly violated by the Town Board of Hempstead.

Description The population of Hempstead, New York, which covers the heart of Long Island’s Nassau County, is 13 percent Black and Latino, but all of its six Republican council members lived in predominantly white neighborhoods. In February 1997, a federal judge ordered Hempstead to replace its at-large voting system with six geographic districts, saying the current system “invidiously excludes Blacks from effective participation in political life.”

The original class action suit was filed by the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR) in 1988, alleging that the at-large electoral system diminished the voting power of Blacks and Latinos in Hempstead in violation of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, as well as the Fifteenth, Fourteenth, Thirteenth and First Amendments. Hempstead has a history of racially polarized voting, leaving candidates of color unable to obtain sufficient votes outside their communities to win election.

A map presented by CCR’s expert witnesses dramatically illustrated the near-total residential segregation in the township—“just like apartheid in South Africa”, according to a lawyer for the plaintiffs—a factor that ironically could make it easier to design a single electoral district where people of color may elect someone of their own choice, even by the standards of recent court decisions restricting the scope of the Voting Rights Act.

Hempstead has a poor record on race: the township was still using a literacy test for voters in 1971, several years after Congress outlawed such tests. Hempstead officials have refused to discipline employees who used racial slurs, have no affirmative action program or city human rights commission, and have never issued any resolution in support of minority issues.

“This case is not about electing a Democrat,” plaintiff lawyer Randolph Scott-McLaughlin told the appeals court. “It is about allowing minorities to acquire the opportunity to nominate and elect the candidate of their choice. Now, they don’t have a choice.”

The Court of Appeals echoed this sentiment in its decision: “Without access to the Republican slating process, Blacks simply are unable to have any preferred candidate elected to the Town Board, given the historical success of the Republican Party in all Town Board elections.”

The U.S. Supreme Court declined to review the decision of the Second Circuit Federal Court of Appeals affirming the district court’s finding that the voting rights of minorities had been flagrantly violated by the Town Board of Hempstead.